By Nelly Childress

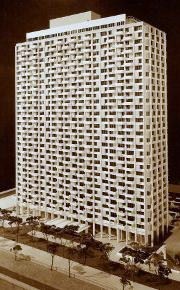

Hopkinson House was conceived in conjunction with a wide-sweeping civic project to restore historic sections of Philadelphia to their vanished grandeur. Hopkinson House is considered a modern monument to the success of a vision that Charles E. Peterson, Judge Edwin O. Lewis, Mayor Richardson Dilworth, Senator Joseph S. Clark, Jr. and City Planner, Edmund Bacon had: the conversion of the Society Hill area from a slum to the showcase renowned as one of the country’s most successful urban renewal projects.

As early as 1955, a syndicate headed by Albert M. Greenfield envisioned building a hotel on Washington Square: a plan which never materialized. In 1959, Major Realty Corporation contemplated the development of a high-rise on the not quite yet rehabilitated Washington Square. Hopkinson House was the name selected by the developer to honor Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), a Philadelphian, signer of the Declaration of Independence, a Renaissance man known for painting, musical compositions, and essays as well as for his career as a lawyer and a judge.

Hopkinson House’s architect, Oskar Gregory Stonorov (1905-1970), was a modernist architect and architectural writer. Following studies at the Universities of Florence and Zurich, Stonorov apprenticed with French sculptor Aristide Maillol. In the United States, he worked on the design of housing developments in Pennsylvania with Louis Kahn. Philadelphia architect and future Pritzker Prize winner Robert Venturi worked in Stonorov’s offices.

Hopkinson House’s architect, Oskar Gregory Stonorov (1905-1970), was a modernist architect and architectural writer. Following studies at the Universities of Florence and Zurich, Stonorov apprenticed with French sculptor Aristide Maillol. In the United States, he worked on the design of housing developments in Pennsylvania with Louis Kahn. Philadelphia architect and future Pritzker Prize winner Robert Venturi worked in Stonorov’s offices.

Influenced by the Bauhaus school of design and a disciple of both Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, Oskar Stonorov worked in a modern idiom he endowed with personal flair. Hopkinson House’s exterior distinctiveness comes from the brilliant placement of balconies which gives it an eye-catching staircase pattern. The broad, glassy entrance to the building and its handsome porte-cochère is a gentle welcoming presence that fits with the entire setting of the park.

Stonorov’s connections to Italy are evident as one enters the outer lobby paved with Italianate terrazzo, its walls and support columns covered by complementary white marble lightly striated with a brushing of grey. In contrasting darkness, textured bronze sheathes the back wall, its surface divided into decorative, trompe-l’oeil rectangular panels. Both marble and bronze continue through the passageway into the inner lobby, framing the elevator banks and bursting to life in an imposing cycle of bas-reliefs that represent the Four Seasons. Personified as women they are Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. The virtuoso bronze caster who could depict female clothing of filmy transparency in a medium so dense and heavy was one of Stonorov’s friends, the Tuscan Jorio Vivarelli.

Edmund Bacon said: “Because Oskar Stonorov was both an architect and a sculptor, he was able to combine art with building in a marvelous way.” The inner lobby is colorfully dominated by Philadelphia Panorama, a mural by American painter Lucius Crowell – a realist painter who enjoyed depicting the everyday world with a touch of romanticism. His major exhibitions included the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a one-man show at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts as well as others in Washington and Chicago where he was born.

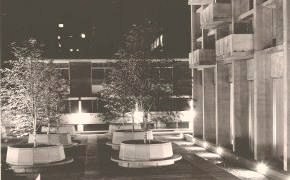

Framed by glass doors directly ahead is Stonorov and Vivarelli’s fine sculptural group of two bronze reclining figures, Adam & Eve, the central focus of the Stonorov’s courtyard designed around it. The work, at once playful, dramatic, and romantic represents Eve with an alluringly recumbent position while Adam rests his head on her right shoulder. In the words of Edmund Bacon, it provides “a most satisfactory conclusion to the art trip.” Extensive restoration work concluded in 2014 rejuvenated the sculpture for posterity.

Fresh air and recreational space meant so much to Oskar Stonorov, he not only included the ground floor plaza but created niches for community gathering on Hopkinson House’s penthouse floor and roof. On its highest floor, the building boasts a large room that takes up practically the entire floor in one sweep and is all windows on its south side. Since 1963, events of all kinds, ranging from family reunions and large social functions to civic gatherings and art exhibits have been held in what was originally called the “skylarium,” now known as the Solarium. At the Solarium’s western end is a door by which people have access to a wide terrace and a staircase to the roof, both of which offer breathtaking views of Philadelphia. On the roof itself, Stonorov placed a swimming pool and sundeck.

Worthy of note too, the architect designed one of Philadelphia’s first buildings with an incorporated garage that allows immediate access to the building. He also included a large, well-planned laundry room at the basement/garage level. Hopkinson House’s northern side features one asset Stonorov certainly considered while executing his concept – Washington Square, which sits as a virtual front lawn. The architect designed a congenial multi-family apartment complex, creating felicitous properties for private clients – thus the long but functional corridors or hallways leading from the elevators to the apartments. (This allowed for additional closets and larger rooms.) A promotional brochure at the time boasts: “Most important of all are the individual apartments, translating into reality your innermost wishes for everything good and in good taste. Truly, ‘at the cross-roads of America’s heritage,’ a new way of life has been created for you. Hopkinson House is its name; serenity and graciousness its theme.”

Worthy of note too, the architect designed one of Philadelphia’s first buildings with an incorporated garage that allows immediate access to the building. He also included a large, well-planned laundry room at the basement/garage level. Hopkinson House’s northern side features one asset Stonorov certainly considered while executing his concept – Washington Square, which sits as a virtual front lawn. The architect designed a congenial multi-family apartment complex, creating felicitous properties for private clients – thus the long but functional corridors or hallways leading from the elevators to the apartments. (This allowed for additional closets and larger rooms.) A promotional brochure at the time boasts: “Most important of all are the individual apartments, translating into reality your innermost wishes for everything good and in good taste. Truly, ‘at the cross-roads of America’s heritage,’ a new way of life has been created for you. Hopkinson House is its name; serenity and graciousness its theme.”

In November of 1962, the first residents moved into the completed lower floors. By the middle of 1963, all 33 floors of Hopkinson House were completed and the 536 apartments were beginning to fill with occupants from the city’s professional and business classes. The building remained a rental apartment dwelling for 18 years. In 1980 it was converted into a condominium.

The conversion from rental to condominium resulted in some changes of the original design of the lobbies, the “Tree Court” now the courtyard, the corridors/hallways and of many of the apartments. A moat that ran around the perimeter of the plaza has been replaced by flower beds along its north, south, and west sides. The stately evergreen trees and planters that populated the tree court were removed. On the eastern wall is now a fountain which fits well into the plaza’s design.

Although some of the original art work was removed during the condominium conversion, the more permanent work of Stonorov and his collaborators will be preserved for the life of Hopkinson House. Statutes passed in 1963 as part of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority’s One-Percent Fine Arts Program stipulate an owner must “preserve, protect, and permanently display the work of art in the space for which it was originally created and intended.” They further state “the work of art shall remain permanently in place, intact and shall be for all purposes a part of the real estate.”

In many ways, Hopkinson House is a vision fulfilled beyond what anyone could have imagined in 1962. Hopkinson House, opening in a questionable neighborhood, was an experiment, a risk. It has gone from being a pioneering venture to an elegant, venerable fixture on Washington Square. It paved the way for much that followed it.

Note: This document summarizes information from the booklet entitled: Hopkinson House: A Living Monument to Modern History by Neal Zoren. The booklet was published on the occasion of the Hopkinson House 35th Anniversary celebration, held in 1998. Additional information was taken from the Hopkinson House Exhibit: The Way We Were, which was displayed in the Solarium in January, 2008, and from writings by Victoria Kirkham and Jim McClelland.

A view of Hopkinson House during the final phase of construction in November, 1962.

A view of Hopkinson House during the final phase of construction in November, 1962.

An early promotional shot of the lobby used to portray the benefits of a high-rise lifestyle.

An early promotional shot of the lobby used to portray the benefits of a high-rise lifestyle.

The rear courtyard plaza showing the original “Tree Court” and moat.

The rear courtyard plaza showing the original “Tree Court” and moat.